This content was originally published in Oilman Magazine.

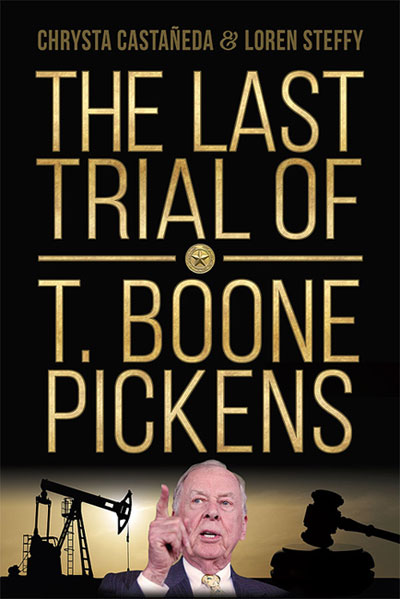

In November 2016, a jury in Pecos, Texas, delivered a $146 million verdict on behalf of my client, Mesa Petroleum Partners, run by the legendary Texas oilman T. Boone Pickens.

It should have been the end of a hard-fought legal battle that had already taken too long and taken too much out of my then 88-year-old client. The jury unanimously found that the defendants in the case had breached their agreement to give Mesa rights to 15 percent of certain properties and wells in the Red Bull area of West Texas’ Reeves and Pecos counties.

But litigation almost never ends quickly, and this case was no exception.

Pickens had suffered a mild stroke during the month-long trial, but he nevertheless insisted on being present for most of the testimony. He was heavily invested in this case. He’d spent millions on legal and expert fees, of course, but he was also invested to the core of his being. This was the biggest oil and gas play of his life. It was a big deal that capped a lifetime of big deals and he’d been determined to be there.

Verdict Not the Conclusion It Should Have Been

A case isn’t over when the jury renders a verdict. The judge must still enter judgment based on that verdict. Sometimes, that can take a few weeks or months, because the losing parties will file motions to complain about the result. Not surprisingly, that happened in this case. The defendants reiterated the same challenges to the damages that they had litigated during the trial. The operator argued that it hadn’t been grossly negligent, nor had it acted with intentional misconduct, and that it should be let out of the case entirely.

One year later, the judge finally entered the judgment, but not before we had to go to the state appeals court in El Paso and ask the justices to force his hand. The appeals court ruled that more than enough time had passed to be able to enter the judgment and told the judge to get it done. He finally did in December 2017 — more than a year since we’d first holed up in Pecos.

The judge let the operator off the hook and I still don’t understand why. I know the arguments it made, hundreds of pages of them, but I don’t know which ones the judge found persuasive. The other defendants, however, still owed us about $136 million plus interest, the amount of the verdict that was left after the operator’s share was removed.

A Texas-Sized Fall

A few months after the judgment was entered, we mediated the Red Bull case. We had set up the mediation before the judge entered the judgment and, even after it was entered, everyone seemed eager to settle rather than endure years of appeals. The parties took two days to mediate and Mesa reached an agreement with the defendants to settle it all.

I felt like we were holding most of the cards at the mediation except for the most critical one: after the stroke he suffered during the trial, Pickens’ health began to falter. He had several more strokes, and then what he would describe to me as a “Texas-sized fall” in which he hit his head. I knew that even though we’d prevailed in Pecos, the cycle would continue with appeals that stretched through the Texas Supreme Court. This would undoubtedly take years more and Pickens wouldn’t live to see the end.

We settled for a confidential amount and most of the team was satisfied. Two of us weren’t: Pickens and I. I saw him regularly after that, heading up to his office about once a month for lunch. Every time I did, he asked me if he’d done the right thing. He wondered if he should have appealed the rulings we disagreed with and litigated another trial again after the appeal sorted out the legal points. But in the end, I assured him he’d made the right choice. I believed in my heart that he had. I didn’t tell him that I feared he wouldn’t live to see a retrial, but I suspected he knew my thoughts. He talked a lot, more than I ever remember, of how he was in the “fourth quarter” of his life. He’d mostly recovered from the stroke, but it served to remind him of his own mortality.

An Indelible Imprint

For my part, I wanted to take the case to the Supreme Court to get the law straightened out, to set the record straight on how companies are supposed to treat investors in oil and gas deals like these. I may never get that chance.

T. Boone Pickens died on Sept. 11, 2019, at the age of 91, leaving behind an unforgettable legacy, and an indelible imprint on my life and career. Cases like the Red Bull just don’t come along that often.

Nor do clients like T. Boone Pickens.